Operational Space Control#

The goal of operational space control (OSC) is to control the robot to track the desired end-effector pose \(\boldsymbol{x}_d\) and velocity \(\boldsymbol{\dot{x}}_d\) given in the operational space. Consider a a \(n\)-joint robot arm without external end-effector forces and any joint friction. The equation of motion of the robot arm is

The controller we want to design is in the general form of

i.e., the controller takes as input the robot arm’s current joint position \(\boldsymbol{q}\), current joint velocity \(\boldsymbol{\dot{q}}\), the desired end-effector pose \(\boldsymbol{x}_d\), and desired end-effector velocity \(\boldsymbol{\dot{x}}_d\), and outputs the joint torque \(\boldsymbol{u}\).

The closed-loop dynamics with controller is

We define the end-effector pose error:

and end-effector velocity error:

with with \(\boldsymbol{x}\) the current/actual robot end-effector pose, and \(\boldsymbol{x}\) the current/actual robot end-effector pose.

Controller 1: PD Control with Gravity Compensation#

Given a stationary end-effector pose \(\boldsymbol{x}_{d}\) (\(\boldsymbol{\dot x}_{ d}=\boldsymbol{0}\)), we want to design a controller (65) such that from any initial robot configuration \(\boldsymbol{q}_0\), the controlled robot arm (66) will eventually reach \(\boldsymbol{x}_{d}\). That means

PD Control with Gravity Compensation

The controller for PD control with gravity compensation follows

with \(\boldsymbol{K}_{P}\) and \(\boldsymbol{K}_{D}\) are positive definite matrices.

Lyapunov stability proof for PD controller (click to expand)

Below, we will prove (69) is stablizing the robot to the desired end-effector position, based on the Lyapunov method (see background of Lyapunov method in Numerical Inverse Kinematics).

First, we take the vector \(\begin{bmatrix}\boldsymbol{e}\\ \boldsymbol{\dot{q}}\end{bmatrix}\) as the system state. Choose the following positive definite quadratic form as Lyapunov function:

with \(\boldsymbol{K}_{P}\) a positive definite matrix.

Then,

Since \(\dot{\boldsymbol{x}}_{d}=\mathbf{0}\),

and then

Similar to the derivation in joint space PD controller, we replace \(\boldsymbol{B}\ddot{\boldsymbol{q}}\) in (71) form closed-loop dynamics

and consider the property \(\dot{\boldsymbol{B}}-2 \boldsymbol{C}\) is a skew-symmetric matrix. Then, (71) becomes

which says the Lyapunov function decreases as long as \(\boldsymbol{J}(\boldsymbol{q})\dot{\boldsymbol{q}} \neq \mathbf{0}\). Thus, the system reaches an equilibrium pose, with condition \(\dot{V}= 0\) and \(\boldsymbol{J}(\boldsymbol{q})\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}=\mathbf{0}\).

We consider the non-redundant non-singularity of matrix \(\boldsymbol{J}(\boldsymbol{q})\). Then, the equilibrium condition \(\boldsymbol{J}(\boldsymbol{q})\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}=\mathbf{0}\) means that \(\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}=\mathbf{0}\) and further \(\ddot{\boldsymbol{q}} =\mathbf{0}\). To find the robot equilibrium configuration, we look at (72). With the condition \(\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}=\mathbf{0}\), it follows that \(\ddot{\boldsymbol{q}} =\mathbf{0}\), and then the above becomes

This concludes that the controlled robot arm will asymptotically reach \(\boldsymbol{x}_d\).

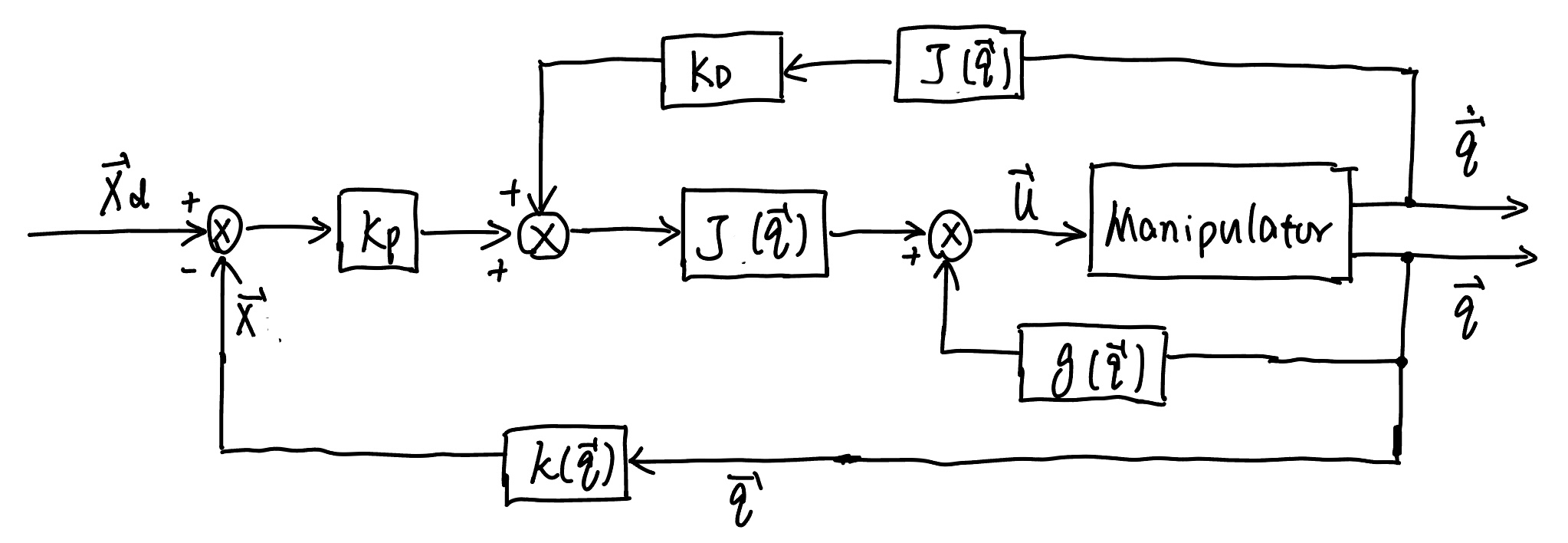

The corresponding control diagram is shown below.

Fig. 69 Block diagram of operational space PD control with gravity compensation#

Controller 2: Inverse Dynamics Control#

One limitation of the OSC PD Control is that the controller can only follow a stationary desired \(\boldsymbol{x}_d\) , but is not good at tracking a fast-changing desired \(\boldsymbol{x}_d\) (i.e., \(\boldsymbol{\dot x}_d\neq \boldsymbol{0}\)). Inverse Dynamics Control can be used.

Inverse dynamics control

with

Here,

with with \(\zeta_i\) the damping ratio and \(\omega_{i}\) the natural frequency.

Stability proof for Inverse Dynamics Control (click to expand)

Plugging (75) to (76) to the closed-loop dynamics (66), we have the following error dynamics

which describes the operational space error dynamics, with \(\boldsymbol{K}_{P}\) and \(\boldsymbol{K}_{D}\) determining the error convergence rate to zero. Typicaly we choose

with with \(\zeta_i\) the damping ratio and \(\omega_{i}\) the natural frequency. Then, the end-effector of the controlled robot arm will behave like a linear second-order (mass-spring-damper) system.

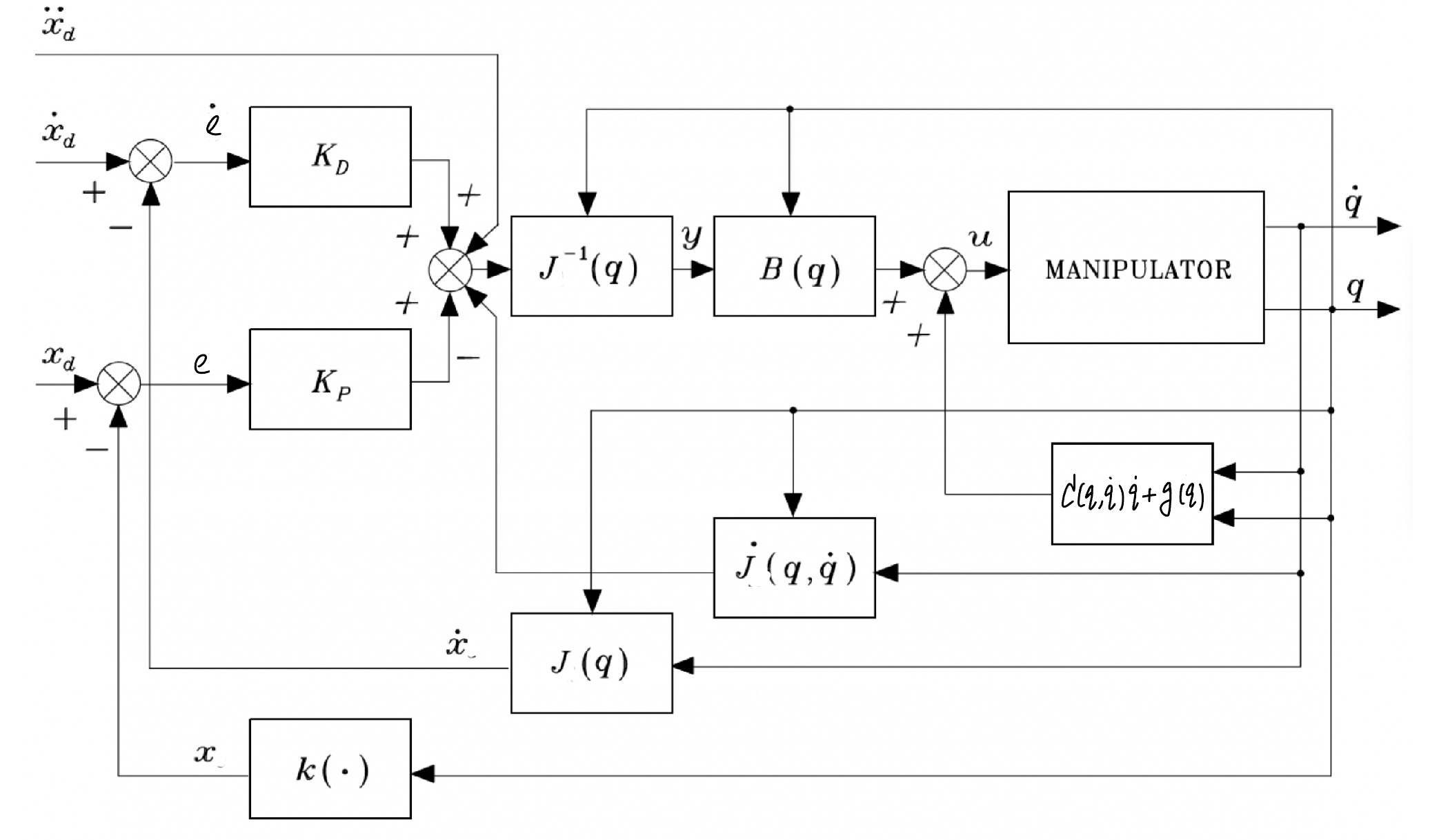

The resulting OCS inverse dynamics control diagram is shown below.

Fig. 70 Block scheme of operational space PD control with gravity compensation#